How Societies Navigated the World before Google Maps

- Unearthed Team

- May 20

- 4 min read

So following the North Star to find the location of the restaurant for dinner might not be on your 2025 bingo card. But how do you think your ancestors got around? Ok, maybe they didn’t exactly need celestial navigation just to grab a bite to eat. But it is true that before the advent of GPS and digital maps, societies across the globe developed ingenious methods to traverse vast landscapes and oceans. These techniques, rooted in keen observation and deep environmental understanding, highlight humanity's adaptability and connection to the natural world. Not only that, but it proves that it is possible to travel without Google Maps, albeit a tad inconvenient.

Celestial navigation and using the stars

This method is probably one of the most well-known. You know when people tell you to just look for the north star if you get lost? Well, there’s a reason for that. For millennia, the night sky served as one of the most reliable kind of compass (probably because for a while, actual compasses weren’t even a thing). Polynesian navigators for instance, would strategically memorise the positions of approximately 200 stars, using their rising and setting points to chart courses across the Pacific Ocean. They even interpreted ocean swells and flight patterns of birds to maintain their bearings, even when stars were obscured by clouds.

In a similar way, Arab sailors employed the kamal. It was a simple device which consisted of a rectangular card and a knotted string to measure the angle of the Pole Star above the horizon. That way, they could determine their latitude during voyages across the Indian Ocean.

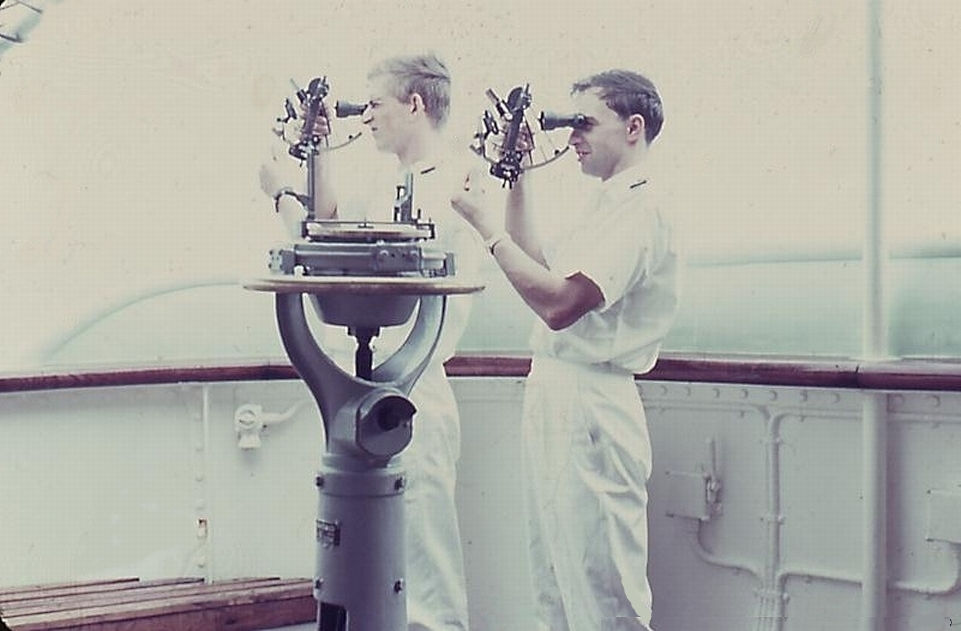

Early navigational instruments

The magnetic compass was first developed in China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). As you can imagine, it was one of those inventions that revolutionised navigation by providing a consistent reference point regardless of weather conditions. Its adoption spread through Arab traders and all the way to Europe by the 12th century, enhancing maritime exploration

Another pivotal instrument was the astrolabe, an ancient device used to measure the altitude of celestial bodies. By determining the sun or stars’ positions, navigators could establish their latitude which was a helpful strategy to navigate in both sea and land journeys.

Reading the environment

Beyond instruments, many cultures relied on environmental cues instead. For example, vikings observed the behaviour of birds. By releasing ravens and following their flight paths, they would eventually manage to locate land. Not much further north, in the Arctic, Inuit communities crafted tactile maps from driftwood. These represented coastlines to guide them through icy terrains.

All they way Down Under, Aboriginal peoples utilised oral narratives called songlines, that mapped the landscape through stories and songs. These songlines served as mnemonic devices, encoding information about routes, landmarks, and resources, and were often mirrored by constellations in the sky (so technically, celestial navigation was always at the forefront of certain navigation techniques).

Early cartography

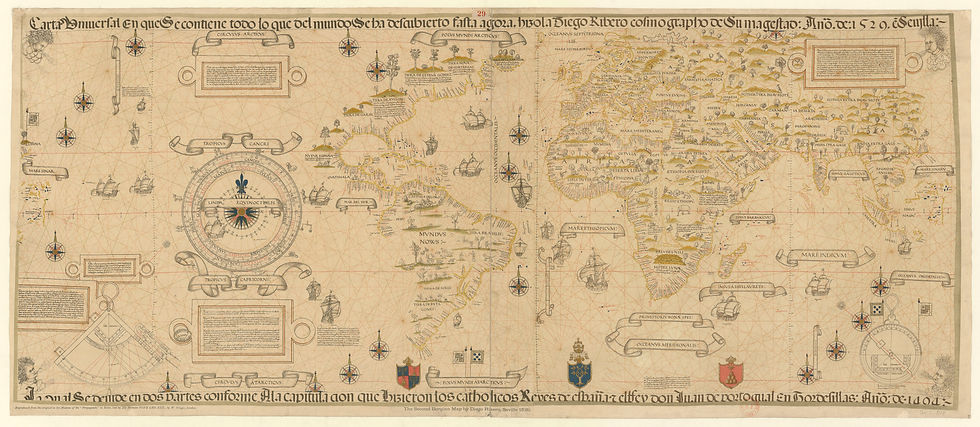

Ancient civilisations had also developed their own mapping techniques to represent their understanding of the world. Chinese cartographers during the Han dynasty created detailed maps on silk, incorporating grid systems and astronomical observations to ensure that the points remained as accurate as possible. In medieval Europe, portolan charts featured rhumb line networks. These are essentially webs of lines radiating from compass roses on a spherical surface. The purpose was to assist sailors in plotting courses across the Mediterranean, clearly wanting to reduce their chances of getting lost in such vast stretches of water.

Whilst it may seem almost impossible to do today, not relying on GPS or technological maps to get around also helps cognitive function. Studies suggest that individuals who navigate without technological aids, such as taxi drivers relying on mental maps, exhibit enhanced spatial memory and are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Clearly, being able to whip out a phone which gives us detailed directions provides us with unparalleled convenience. However, revisiting these ancestral navigation methods can enrich our understanding of the environment and our place within it. In a cheesy way, embracing traditional techniques fosters a deeper connection to the world around us. But in a more scientific way, being able to get around with just brain power, sheer determination and possibly some celestial skills is a great way to improve spatial memory and cognitive function. So maybe next time you think of trying out that new trendy restaurant, try getting there without using your phone.

Comments